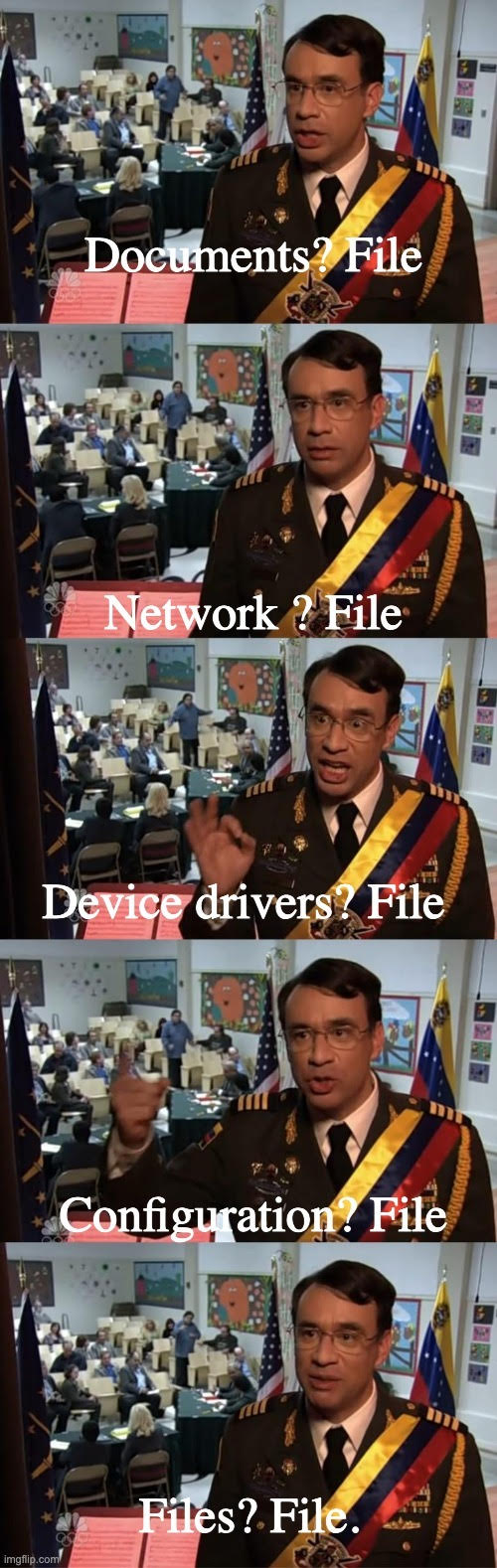

Nothing new under the sun: everything is a file

The Unix revolution was built on a key principle: everything is a file. Now, with the rise of AI Agents, LLMs have access to half a century of file-based arcana. The result? Everything is becoming a file again.

"What has been will be again, what has been done will be done again; there is nothing new under the sun." – Ecclesiastes 1:9

My first contact with computers happened when I was 11 years old. I had an old PC running MS-DOS 5.2 and Windows 3.1. I used it mostly to play games. However, my professional self (30 years later) is happy that just playing games in that era required learning about x86 memory segmentation.

Those were fun times, but I don't even count that as a gateway drug to programming. What got me hooked was what came later: Unix. It wasn't until my first year in high school that I discovered Linux. Once I started college, my interest really piqued. Soon, I was all-in on the history of Unix and would find any possible excuse to play with the SPARC Solaris station parked in the Materials department.

We wouldn't be where we are today without Unix. If you never experienced the old days, it is probably easy to underestimate the significance of Unix. But aside from the C language as a side-effect, Unix gave the world two things:

- The "ship it" idea: Unix introduced man pages that would document the limitations of the tools instead of waiting for perfection.

- The "everything is a file" abstraction, with the concept of pipes gluing tools together.

#The power of files

After I replaced my boring friends with Unix zealots (that's how I like to tell the story – in reality, they all stopped talking to me because I wouldn't shut up about Unix), I kept hearing the phrase: "sed awk cut grep is all you need." It is a beautiful abstraction. It sounds obvious to us half a century later (like most great ideas), but in reality, it's anything but obvious.

Every program understands files. They can write to a file, and they can read from a file. And what that means is that suddenly you have a unified interface across the entire system. A contract that everyone follows, making sure that every other application can consume the results of every other application.

That simple abstraction, a file, allowed for another powerful Unix principle to come to life: "Do one thing, and one thing well." Instead of building a big application, each tool can hyper-specialize. They can do this because they are all inputting and outputting the results of their work as files.

This leads to a combinatorial explosion of what can be achieved, and it all happens through the file contract. Write a couple of bytes here, read a couple of bytes there, and pipes glue them together.

Files are most commonly understood as something that lives in your storage device, like a PDF or a spreadsheet document. But what makes them so powerful is that they are a very simple abstraction: a collection of bytes that can be read from and written to. Soon, Unix would have virtual files all over the place. Ultimately even a network connection in the Unix world could be represented as a file.

#Beyond Unix

Linux took that to the extreme. There is a /proc virtual filesystem with all sorts of information about your Kernel, and the way you read this information is… by reading virtual files (The proc filesystem existed in the original Unices, but it was predominantly simple information about the running processes, as the name implies)

There is also a /sys virtual filesystem where you can get all sorts of information about your device drivers and hardware system. And the way you interact with it is, you guessed it, by reading and writing files.

And we built our world on top of this. Later, we saw similar contracts appearing in other layers (like APIs), but the file was still ever-present. Even in API-based systems, files are still used to configure systems, store code, serve assets, etc.

#Reusability matters

Fast-forward to the AI era, and one thing became clear: LLMs are nice, neat, and cute. But they won't take you anywhere. What truly unlocks the potential for AI is agents, which is a fancy way of saying "a for loop where the LLM uses tools."

As it turns out, LLMs are really, really good at using the tools that have been around for half a century of Unix. The tools that compose together beautifully through the file abstraction. In half a century of Unix, we have accumulated a tool for every conceivable job. Because of their very nature as stream pushers, agents are really really good at using them.

Sure, we can rebuild everything. We can give agents specialized tools that are agent-native. But that would mean throwing all the capital we have accumulated throughout all this time into the void…for marginal gains. We haven't done that with the shape of power plugs, and SQL still reigns supreme (despite the fact that every developer seems to think they know how to do better).

#Modern, Richer Filesystems

Instead, agents will embrace the filesystem. This is already happening, with tools like Claude Code heavily relying on it, and it will happen even more.

However, that doesn't mean filesystems will stay the same. There are two particular trends in the industry now that will apply pressure in the shape of filesystems.

The first is the prevalence of Typescript and browser-based environments as deployment vehicles for agents. Browsers don't really have an easy way to plug into a standard filesystem, and Typescript-based agents are usually deployed into ephemeral environments where a filesystem is not to be taken for granted. That's a side effect of those platforms evolving to provide a function-like environment that connects to a database over-the-wire for its data needs.

The second is the rise of the sandbox as the preferred way to isolate agentic workloads. Sandboxes take virtualized environments to the next level. Environments need to come online in milliseconds as agents spawn sub-agents to go explore the solution space. Attaching traditional filesystems to those sandboxes is just too slow for the speed at which they need to operate.

Two interesting tools that are trying to tackle this are worth mentioning. The first is just-bash by Vercel. The tool provides an emulated bash-like environment for agents written in Typescript, allowing agents to use tooling as if they were operating in a normal Unix shell, wherever they may be executing:

import { Bash } from "just-bash";

const env = new Bash();

await env.exec('echo "Hello" > greeting.txt');

const result = await env.exec("cat greeting.txt");

console.log(result.stdout); // "Hello\n"

console.log(result.exitCode); // 0

console.log(result.env); // Final environment after execution

The second is our very own AgentFS, a tool that maps an entire filesystem into a SQLite file. The filesystem can be isolated between agents (with changes being captured into the file, without harming the original filesystem).

This makes sure that a) the agent can access only the parts of the context it's supposed to access, and b) that it is allowed to operate on the assets freely, knowing that changes are non-destructive.

The SQLite file can be copied or partially copied around by sandboxes and made available instantly as the agents execute. This supports snapshotting (where an agent can save its own state, take a step, and then rollback to the previous file if it makes a mistake) as well as sharing of state between a group of agents.

#Conclusion

What comes around, goes around. As the world changes radically around us, one thing will not change: we build on top of what came before us, and rebuild from scratch at our own peril. The Unix revolution gave us the file abstraction, and for half a century, we built on it.

For AI agents, the question will be: do we tap into the immense potential of all tooling written in the past 50 years, or rebuild everything?

The answer is starting to become apparent.